Jyoti is a sales manager handling a team of fifteen people. She firmly believes in the motto “hard work and success walk hand-in-hand.” She is an optimist and turns every challenge into an opportunity, however, she observes that the graph of her team’s shared efforts is going down. There had been a slump in sales for a couple of months. As she believed that hard work brings success, she came to the conclusion that her team was not working effectively.

It entirely made sense to her as she was noticing a delay in the deliverables from her team. She called a meeting and warned her team to meet the deadlines on time, or else there would be no appraisal in the next quarter. Despite the efforts, there was no increase in sales, and there were more warnings on the way. She decided to consult her higher authority after multiple attempts and learned that the strategy her team was using was not an effective solution to the problem.

Rather than working as a team and finding a solution, Jyoti was adamant that her team was not working in the right direction. Her belief in hard work as a critical metric of success led her to blame her team for slacking while going around the bushes and ignoring the true cause. It is the result of the confirmation bias, that helped Jyoti to support her pre-existing beliefs and give them higher credence than following the facts for a proper solution.

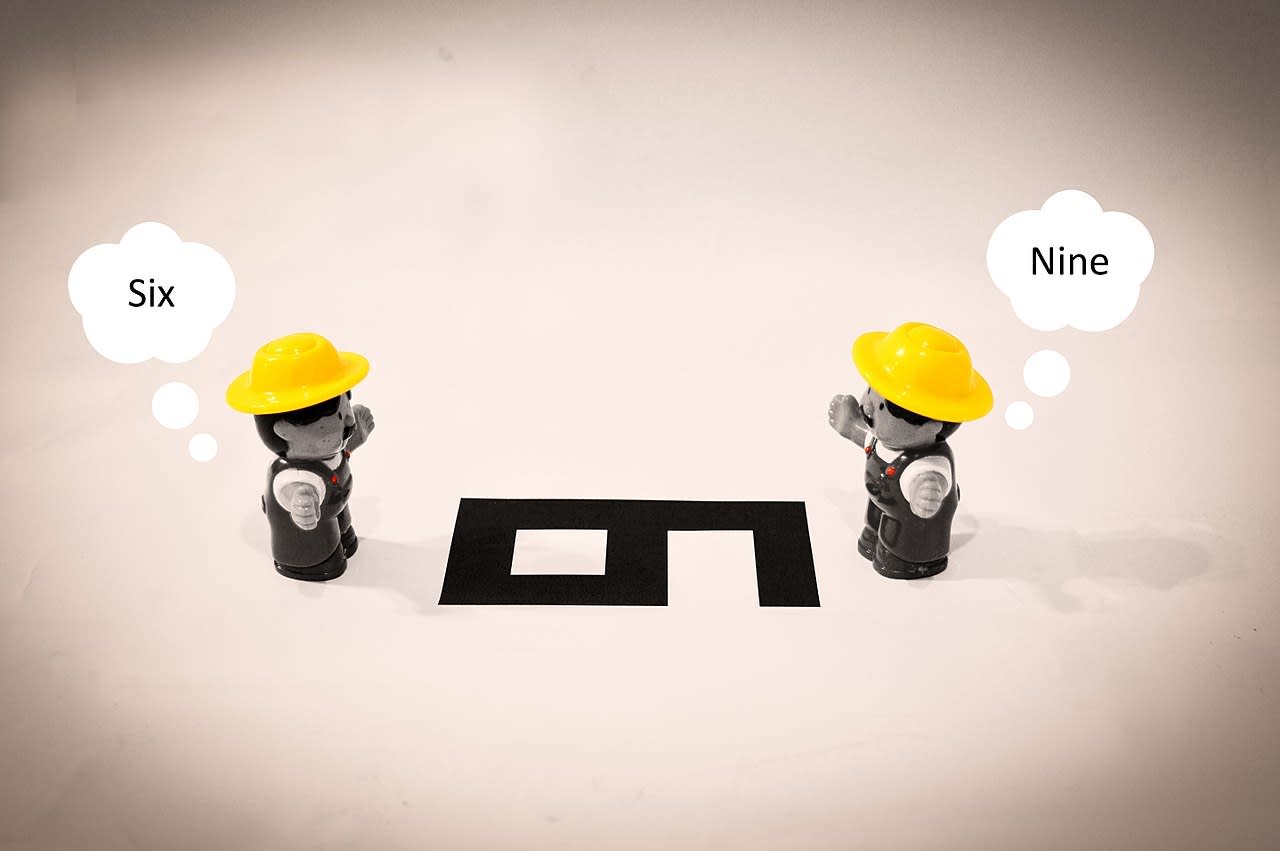

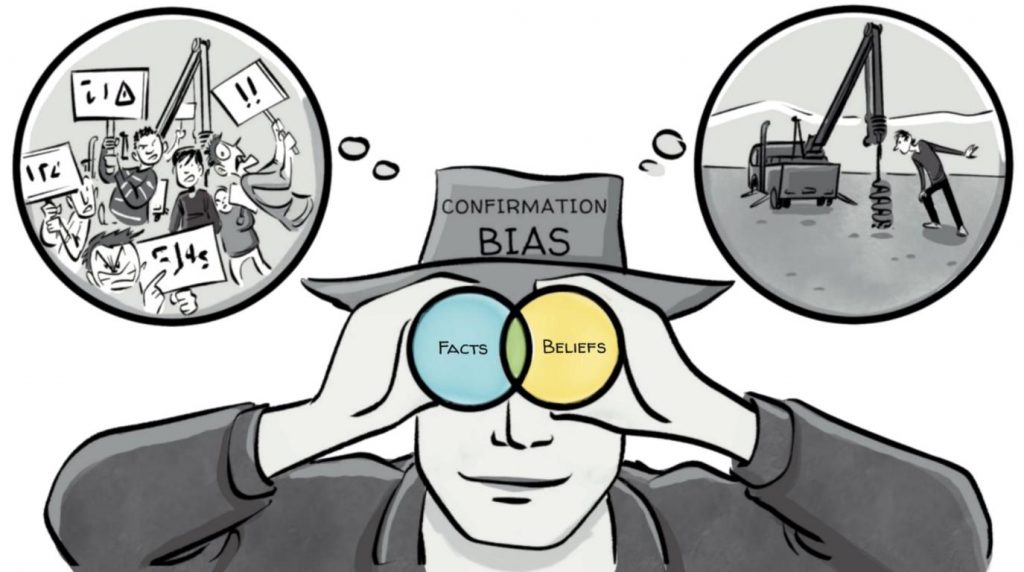

Our tendency to cherry-pick information that validates our existing opinions or notions is known as confirmation bias. Confirmation bias describes how two people with opposing viewpoints on a subject might both see the same information and feel justified by it. When it comes to deeply held, ideological, or emotionally charged beliefs, this cognitive bias is most evident.

What is the source of your beliefs and opinions? If you’re like most people, you consider your beliefs are rational, logical, and unbiased, based on years of experience and objective examination of the facts accessible to you. The reality is we’re all prone to a perplexing condition known as confirmation bias. Our beliefs are frequently established on paying attention to information that supports them while ignoring information that contradicts them.

What Is Its Effect?

The impact of confirmation biases not only affects the way we receive information but the way we comprehend and reminisce it. People who support or oppose a certain subject, for example, will not only seek information to support their position but will also interpret news stories to support their previous beliefs. They will also connect the dots in a way that matches the frequency of their beliefs.

Effect on the System

Individual confirmation bias can have severe collective consequences. If we’re so set in our ways that we only accept facts that confirm them, larger socio-political collaboration (which sometimes necessitates examining different points of view) can be hampered. Our predisposition to prioritize information that confirms our existing opinions and dismiss facts that contradict them may be the source of major social conflicts and stagnant policymaking.

Effect on an Individual

This bias alters the reality from which we draw evidence, it might lead us to make inaccurate decisions. Under experimental conditions, decision-makers are more likely to actively seek information and place a higher weight on evidence that confirms their existing ideas than on evidence that contradicts them. It can be considered a sort of evidence-gathering bias. Conclusions based on biased evidence are more likely to be incorrect than conclusions based on objective evidence. It is due to the fact that they are way off the mark.

Why Does It Happen?

Understandably, we employ this mental shortcut. It takes a lot of mental work to evaluate evidence (especially when it’s intricate or confusing). Our minds seek to take shortcuts whenever possible. This saves time while making decisions, which is especially important when we’re under pressure. Our minds are unprepared to deal with the modern world, as numerous evolutionary biologists have pointed out.

People have had very little new information over their lifetimes for most of human history. The majority of decisions were made for the sake of survival. We are continuously bombarded with new information and must make several complex decisions every day. We have a natural desire to take shortcuts to avoid feeling overwhelmed.

Shortcuts to Save Energy

Consider how our ancestors hunted. They only have a few seconds to decide whether to stand their position or flee as an enraged beast charges toward them. There isn’t enough time to evaluate all of the factors that go into making a well-informed decision. They may run if they see the size of the animal, based on past experience and instinct. The existence of another hunting group, on the other hand, has shifted the odds of a successful confrontation in their favor. Many evolutionary biologists believe that our use of shortcuts to make quick decisions in the modern world is motivated by survival instincts.

Heuristics is the term for these shortcuts. Confirmation bias is debatable as to whether it can be classified as a heuristic. However, one thing is certain: we utilize it as a cognitive tool to find data that best supports our hypotheses. The hypotheses we already have are the most readily available. We frequently need to make sense of the information rapidly, yet it takes time to establish new explanations or beliefs. We’ve evolved to choose the road of least resistance, which is typically the most practical option.

Reaffirmation to Feel Good

This could also explain why confirmation bias manifests itself in groups. Clinical psychologist Harriet Lerner and political psychologist Phillip Tetlock proposed in prominent peer-reviewed research from 2002 that when we engage with others, we prefer to acquire similar opinions in order to better fit into the group.

We all find boasting about ourselves, and discovering that a belief we hold dear is wrong might make us feel that way. As deeply held beliefs often shape our identities, disproving them can be difficult. We may even feel that being incorrect implies a lack of intelligence. As a result, we only cherry-pick information that aligns rather than contradicts our biased opinions. It is also a reason that we reflect confirmation bias because it protects our self-esteem.

In interpersonal contexts, confirmatory thought can lead to “groupthink,” in which the need for group conformity leads to faulty decision-making. While confirmation bias is frequently an individual phenomenon, it can also occur in groups.

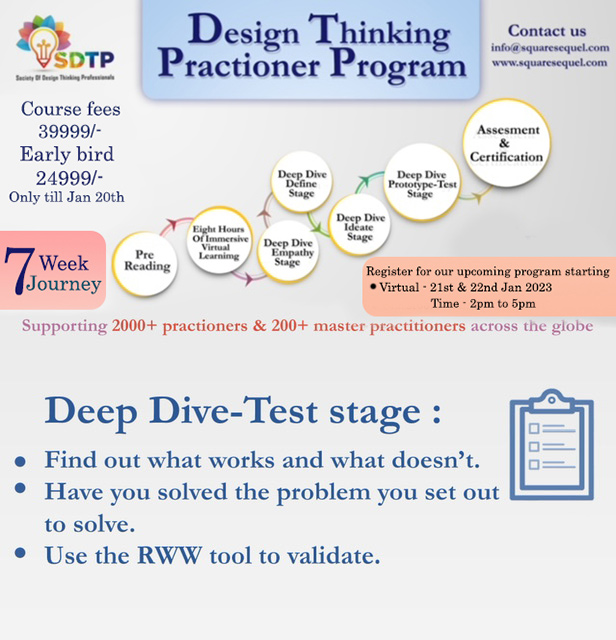

Confirmation Bias and Design Thinking

Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman investigated how alternative phrasing influenced participants’ responses to a hypothetical life-or-death crisis in 1981. 5 Participants in the study were given the option of choosing between two therapies for 600 patients who were suffering from a fatal condition. Treatment A was anticipated to kill 400 people, while treatment B had a 33 percent probability of killing no one but a 66 percent risk of killing everyone.

This option was then offered to participants with either a positive or negative framing, i.e. how many people would live, or how many people would die. When offered positive framing (“saves 200 lives”), 72 percent of participants chose Treatment A; but, when presented with negative framing (“400 people will die”), only 22 percent chose Treatment A.

The participants’ choices in this study demonstrate our proclivity to make decisions based on whether the possibilities are presented with positive or negative meanings, such as a gain or a loss. This is known as the framing effect in psychology, and it has an impact on every element of the design process, from understanding research data to choosing design options.

During design research, framing can take two forms. For starters, how questions are phrased during user interviews or usability testing can have a big impact on how people respond. Secondly, it is how we present research outcomes. Receiving design feedback is another possible entry point for framing during the design phase. Overly precise input might define the problem in a way that limits the design solution or influences it in such a way that other key aspects are overlooked.

How Does A Design Thinking Practitioner Manage Confirmation Bias?

This bias is most likely to arise while we are acquiring information when making decisions. It’s also likely to happen subconsciously, which means we’re not aware of how it affects our decisions. As a result, the first step in avoiding confirmation bias is to recognize that it exists. We are more likely to recognize it in our decision-making if we grasp its effect and how it operates.

Think Through The Context

For team members, especially designers, solving problems when we should be gathering information is a constant struggle. While it may be tempting to leap right into answers, taking a moment to consider context will have a huge impact on how we understand the facts. Only when we’ve spent enough time with the data have we been able to reconstruct useful insights and uncover patterns that aren’t immediately apparent.

Create A Cluster Of More Context

Wait until you have enough data to make an informed judgement rather than making a decision based on how much data you have. Sometimes research reveals areas in which we need to learn more. When you have a clear picture of the problem and enough knowledge to start working on a solution, you’ll know you have enough information to make an informed decision.

Have A Different Perspective

Shifting your point of view is another approach to see if your opinion is being influenced by framing. You can do this by reversing a data point from a success rate to a failure rate, or by describing a problem in the opposite way. The goal is to look at the data from a different perspective in order to prevent overemphasizing or omitting specific facts.

We should focus on starting with a neutral fact basis because bias develops early in the decision-making process. It can be accomplished by having one (or, ideally, numerous) third parties collect facts to create a more objective body of data. When formulating hypotheses based on the gathered data, decision-makers should engage in inter-personal dialogues aimed at recognizing individual cognitive bias in hypothesis selection and evaluation. While it is unlikely that confirmation bias can be totally eliminated, these techniques can help people manage their cognitive bias and make better decisions.

The reality is we all incur confirmation bias. Even if we think we’re very open-minded and merely look at the facts before concluding, there’s a good chance we’ll wind up with some bias in our judgement. Combating this innate tendency is quite difficult. That said, if we understand confirmation bias and accept that it exists, we can attempt to notice it by cultivating an interest in opposing viewpoints and paying attention to what others have to say and why they say it. It can help us see issues and beliefs from a different perspective, albeit we must remain vigilant in avoiding confirmation bias.

https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/confirmation-bias

https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-a-confirmation-bias-2795024

https://jonyablonski.com/articles/2021/cognitive-bias-and-the-design-process-part-1/

https://techindc.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/shutterstock_654405619-1024×576.jpg

https://scx2.b-cdn.net/gfx/news/2018/confirmation.jpg

https://sproutsschools.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Scene-5-20-1024×572.jpg

https://d2iqkqo4ohnqnu.cloudfront.net/2021/06/hotelintel-thumbnail-1-1.jpg

Written By: Jimmy Jain

Edited By: Afreen Fatima

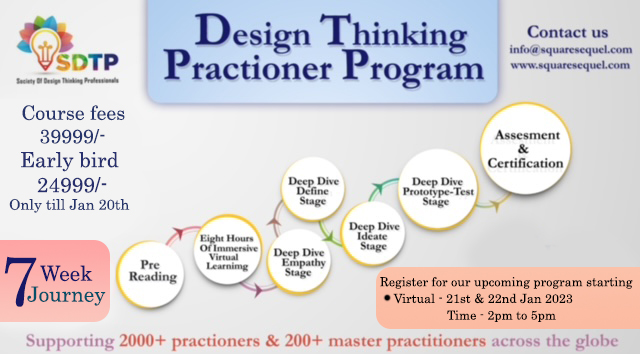

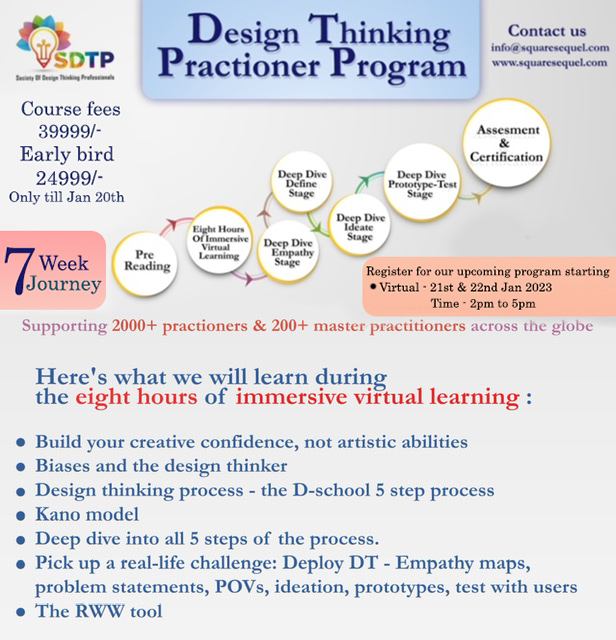

Society of Design Thinking Professionals