Aman woke up one morning, and his head popped off the pillow in a panic. The long-awaited research report he had been chipping away at slowly was due in four days. A cold sweat settled on his skin as he sat down to work out a research report that was probably going to fall short of his faculty’s expectations. At this point, he was thinking that he needs more time for the same report he anticipated completing in the stipulated time. He now envisions his mentor shaking their head in disapproval and wincing at him.

Now Aman is cursing himself for not start working on the research on time.

If we flip the situation and now Aman has a complete month to prepare his research report. He thinks he has a lot of time, “What a relief – now I can sleep it off.” Hold on! A voice inside his head shocked him and said, “Before you relax and hit the snooze button, you need to pull yourself together and learn more about this career-disrupting process, or it will sink your sailing ship gradually.”

People exaggerate their confidence in their plans – something we call the planning fallacy. The existence of the plan tends to induce overconfidence.” — Daniel Kahneman

No one sets out on a new endeavor with the expectation that it would not go as planned — yet it occurs time and time again. Why do so many of us become caught in this cycle? Our perceptions of the amount of time we have available, our ability, and any potential impediments are all biased. The planning fallacy is a phenomenon that affects professionals at all levels and across all industries.

Even when it clearly contradicts our previous experiences, research reveals that we often underestimate the time and hurdles entailed in completing a task. This is due to our optimism bias, which is our natural desire to believe that the future will be better than the past.

What Is Its Effect?

Wishful thinking is the starting point for the planning error. Minor (and even severe) delays aren’t taken into account. At the first glance, delaying work does not appear to be a bad idea. We unknowingly find ourselves in last-minute, or worse, past-deadline scenarios because we tend to underestimate how long it will take to finish work and any associated risks and unplanned expenditures.

Effect on the System

Everyone is affected by the planning fallacy, whether they are an undergraduate student, a city planner, or the CEO of a company. When it comes to large-scale initiatives, from disruptive construction projects to costly business mergers, many people’s lives (not to mention a lot of money) are on the line, and bad planning has severe economic and social effects.

Effect on an Individual

The planning fallacy, as its name implies, can cause us to plan badly for the future, forcing us to make judgments that overlook reasonable assessments of a task’s demands (be it time, money, energy, or something else). It also causes us to discount danger and luck in favor of focusing solely on our own ability—and most likely an unduly optimistic estimate of our abilities at that.

Regardless of the cause, the planning error has the potential to cause significant harm. A missed deadline can have a negative impact on your professional reputation as well as cost you money. It can also wreak havoc on your routine. If you miss a deadline, you’ll have to reschedule your next project.

Why Does It Happen?

The planning fallacy arises from our strong pattern to be optimistic, especially when it comes to our abilities. We have positive expectations of the world and other people; we are more likely to remember happy events than negative ones; and, most importantly, we prefer to make decisions based on positive information.

When it comes to assessing our abilities, we have an especially poor track record. A study asked prospective university students to predict their academic performance in comparison to their peers. Participants expected to outperform 84 percent of their colleagues on average. Of course, this amount may or may not be accurate for some pupils, however, it is merely possible for everyone to be in the top 16 percent.

It means when we set out to plan a project, we are more inclined to focus on anticipated positive results rather than potential hazards, and we are more likely to overestimate our (and our team members’) ability to achieve particular objectives. While excitement is essential for any business, it may become toxic if it is pursued at the price of reality.

Anchoring To The Original Plan

Anchoring is particularly difficult if our initial plans were overly hopeful. We still feel linked to those data as we try to review them, even if our initial projections were hugely incorrect. As a result, we make insufficient revisions to our plans as we go along, choosing modest tweaks over large alterations (even if major changes are necessary).

Ignoring The Stumbling Stones

One example of this is what is known as competitor neglect in the business world, which describes how corporate executives fail to foresee how their competitors will behave since they are focused on their own company. When a corporation decides to enter a fast-growing market, for example, it frequently overlooks the fact that its competitors are likely to do the same, resulting in a risk underestimate.

When it comes to our accomplishments and disappointments, we frequently make attribution errors. We attribute positive outcomes to our talents and hard work, whereas negative outcomes are attributed to causes beyond our control. This makes us less likely to consider earlier failures: we believe those occurrences were not our fault, and we persuade ourselves that the external circumstances that caused us to fail would not occur again.

Under Social Pressure

The planning fallacy can be extremely harmful due to organizational pressure to complete projects fast and without difficulties. Workplace environments can be fiercely competitive, and individuals who express less enthusiasm for a project or insist on a longer deadline than others may pay a price. Executives, on the other hand, may prefer the most unduly optimistic predictions above others, incentivizing individuals to participate in faulty, intuition-based planning.

The planning fallacy has effects on both our professional and personal lives, encouraging us to invest our time and money in doomed initiatives and keeping us bound to them for far too long. The prevalence of this bias has been established by research: In the business world, it has been discovered that over 80% of new businesses fail to meet their initial market-share goals. Meanwhile, in the classroom, students indicate that around two-thirds of their assignments are completed later than planned.

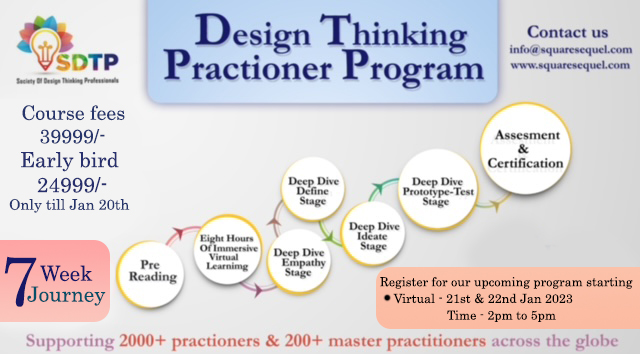

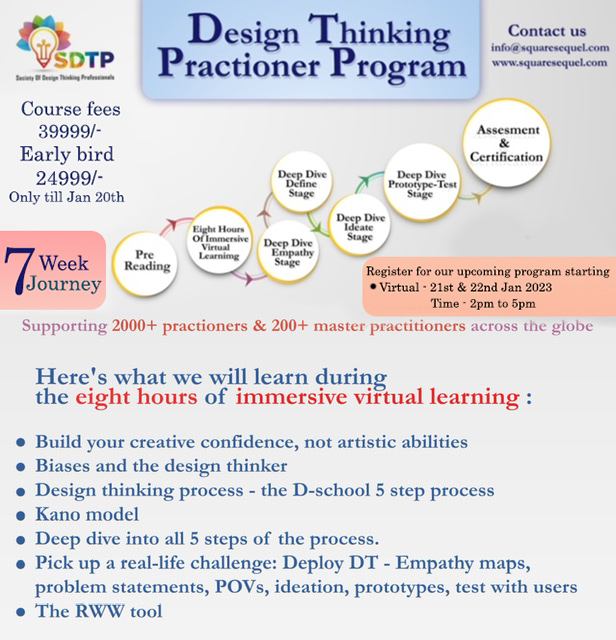

Planning Fallacy And Design Thinking

When the factors of a good solution change as you get started, planning ahead of time is pointless. Fixed specs are only useful in the past because the delivery will vary over time. Consider a software product that is scheduled to be released in 2020. The plan took a year to implement, and the market shifted during that period. The project is put on hold, or worse, you’ve started a two-year project with 40 employees working on something that will never be considered valuable. The building, as well as the organization, loses motivation and knowledge.

On the contrary, design thinkers apply design thinking principles naturally to the process of making something. Their goal is to create a product, and put it out there to test its reliability. May it be a preto or prototype, it should reach the real people in the real world. They deal in tangible concepts and do not dwell on the research before getting started.

Better still, they allow people to use, critique and learn from it while iterating immediately. The only way to stay competitive is to move quickly and put research into practice. They are confident in their decisions, regardless of when it occurs. They have the grace to recognize that mistakes are inevitable and part of the process.

How Does A Design Thinking Practitioner Manage Planning Fallacy?

We have to think beyond just being aware of the planning fallacy to prevent it from occurring. Even though we have this knowledge, we can still fall into the trap of assuming that the rules will not apply to us this time. Most of us prefer to trust our instincts, even if they have been proven to be incorrect in the past. We may plan around the planning fallacy by incorporating procedures into the planning process that will assist us in avoiding it.

Look out for an Outside View

Have you ever thought about how much easier it is to give advice than it is to receive it? When we try to schedule our time, the same thing happens. When we’re anticipating how long a task will take someone else, studies demonstrate that the planning fallacy disappears. It is known as Taking an “outside view.”

As a result, we’re overconfident in our own abilities while being more realistic with others. To overcome this, we can employ “Reference class forecasting,” which is a fancy way of saying “shift your thought process from “how long has this taken me in the past?” to “how long does this type of project take individuals like me?”

Set Intentions to Implementations

Research conducted in the Netherlands illustrated another technique for overcoming the planning fallacy, in which participants were given a writing project and told to complete it within a week. Two groups of participants were formed. Both groups were given instructions to set goal intentions, indicating when they planned to begin writing the paper and when they expected to conclude it.

The second group, on the other hand, was given implementation instructions, including what time of day and where they would write, and was asked to imagine themselves carrying out their plan. Setting precise implementation objectives resulted in much more realistic goal-setting, according to the researchers. Simultaneously, doing so did not dampen the participants’ optimism; on the contrary, it increased their confidence in their capacity to achieve their objectives.

The planning fallacy describes our tendency to underestimate the length of time it will take to complete a task, as well as the expenses and dangers involved—even though our experiences contradict this. Breaking down large projects into their component pieces and then planning for the completion of the smaller subtasks rather than the project as a whole is a related method. As awful as we are at estimating the amount of time needed for relatively major projects, research has shown that we are considerably better at preparing for small ones: our estimates are often surprisingly accurate, and at worst, they are overstated. As a result, this is a considerably safer strategy: In practice, it’s much preferable to give a project too much time than too little of it.

https://blog.rescuetime.com/planning-fallacy/

https://medium.com/hellogreatworks/learning-a-design-mindset-76f96478b31d

https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/planning-fallacy

https://nesslabs.com/planning-fallacy

https://blog.trello.com/hubfs/2017-09-26_How-To-Deal-When-Youve-Overextended_01cover_r01TP.png

https://www.projectmanager.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/190924_Blog_Feature_Time_Estimation.jpg

https://blog.doist.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/7CognitiveBiases_thumbnail-1088×618.png

https://miro.medium.com/max/1200/1*ybX7p_Ex7rpmS5AXi-0f0g.png

Written By: Jimmy Jain

Edited By: Afreen Fatima

Society of Design Thinking Professionals