Rajeev decided to purchase a new car, and according to his online research the average price of the vehicle he is interested in is INR 11,80,000. When he compared the rates at the local car lot, the dealer gave him an offer of INR 11,65,000 for the same car. The local car lot offer seemed quite acceptable to him as it was INR 15,000 less than he was expecting to pay. However, Rajeev tried some other agencies too, and the car dealer across the town was offering the same car for just INR 11,30,000, and that was INR 35,000 less than the price he found online.

Since his initial research indicated that INR 11,80,000 was the average price of the car, the first offer he had his eye on felt like a good deal. He was open to exploring better options and found out that the local dealers are offering a great deal for the same car. It made him choose a better option from the information he already had, that served as an anchoring point in his mind. As anchoring bias suggests that we tend to go with the first bit of information we learn about.

Anchoring bias is a cognitive bias in which we place too much emphasis on the first piece of information we find about a topic. We interpret newer information from the reference point of our anchor when making plans or making estimates about something, rather than seeing it objectively. This can skew our perceptions and hinder us from changing our plans or forecasts as frequently as we should.

This type of confirmation bias operates by training the brain to believe that an initial value must be important, even though including it in decision-making is utterly nonsensical. Anchoring bias occurs when you make a decision regarding the ultimate result based on the beginning of a conversation or another component that isn’t necessarily related. This cognitive bias has the potential to have a substantial impact on how we reason about the world.

What Is Its Effect?

Anchoring bias is one of psychology’s most powerful effects. Many research has corroborated its findings, demonstrating how people might become anchored by ideals that aren’t even related to the activity at hand. Anchoring appears to be profoundly ingrained in the human mind, based on its widespread use. Its causes are still being discussed, however, recent data suggest that it occurs for various reasons depending on the source of the anchoring information. We can acquire a variety of values or bits of knowledge, whether we created them ourselves or were given them to us, and for a variety of reasons.

Effect on the System

Many other cognitive biases, such as the planning fallacy and the spotlight effect, are assumed to be driven by anchoring bias. Anchoring has even been shown to impact judicial decisions, with research indicating that giving an anchor can influence the punishments handed down by juries and judges.

Effect on an Individual

When we become fixated on a certain person or course of action, we begin to filter all new information through the framework we created in our heads, distorting our view. This makes us hesitant to make major modifications to our plans, even when the situation requires it.

We activate other pieces of information that are consistent with the anchor as we create our mental model and test the anchor on it. As a result, all of this data becomes primed, making it more likely to influence our decisions. Anchoring bias should be stronger when the primed knowledge is appropriate to the job at hand, because the activated information dwells within our mental model for a certain notion.

Why Does It Happen?

People were asked for the last two digits of their social security number in one survey. Following that, they were shown a variety of objects, including computer equipment, wine bottles, and chocolate boxes. Participants stated whether they would be ready to pay the sum generated by their two numbers for each item. If someone’s number ended in 34, for example, they would answer if they would pay $34 for each item. The researchers then asked the subjects the highest sum they would be ready to pay.

Even though a person’s social security number is just a bunch of digits, those digits have an impact on their decision-making. When compared to individuals with lower numbers, people with higher numbers were willing to spend much more on identical things. When anchors are obtained by rolling dice or spinning a wheel, and when researchers tell participants that the anchor is irrelevant, anchoring bias persists.

A range of characteristics, such as mood, personality, and experience, might influence the anchoring bias. Different characteristics of these elements can either increase or diminish the effect of this bias.

Personality

Personality has also been demonstrated to have an impact on anchoring bias (Caputo, 2014). Being amiable and open to new experiences, in particular, are two personality attributes that can make people less prone to this bias (Caputo, 2014). While personality qualities are mostly genetic, people can seek to apply these attributes to a variety of settings in order to avoid the anchoring bias.

Mood

The anchoring bias can be influenced by mood, according to two tests done by researchers Englich and Soder in 2009. (Englich & Soder, 2009). They discovered that a pleasant attitude can help to avoid the anchoring bias (Englich & Soder, 2009). This adds to the long list of advantages that being in a good mood offers over being in a bad mood.

Furthermore, Bodenhausen et al. observed in two research published in 2000 that individuals who are unhappy are more prone to have anchoring bias than people who feel neutral (Bodenhausen et al., 2000).

Experience

Experience is a third component that influences the anchoring bias (Welsh et al., 2014). Researchers discovered that participants’ skills in a card game improved over time, implying that experience affects anchoring bias (Welsh et al., 2014). This demonstrates that the more someone engages in a certain activity, the less likely they are to encounter anchoring bias in that activity.

Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, two of the most famous pioneers in behavioral economics, came up with the initial explanation for anchoring bias. Tversky and Kahneman postulated that when people try to make estimates or forecasts, they start with some initial value, or starting point, and then adjust, according to a 1974 study titled “Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases.” Anchoring bias occurs when the modifications are insufficient, causing us to make wrong conclusions. It was then known as the anchor and adjust hypothesis.

Anchoring Bias And Design Thinking

Anchoring has the risk of causing fixation and trapping people in a particular way of thinking about a problem. What makes anchoring so difficult is that it might be difficult to recognize as a bias. When articulating (for example) users’ needs, one incorrect term can lead people down the wrong path.

A customer is looking for a way to improve the user experience for a specific application. During the project manager’s most recent team assessment, he discovered a few client complaints about application downtime. As a result, he feels that cutting down on downtime will improve the user experience. Although application uptime may be a basic need for the customer, his expectations for improving the user experience may be quite different. What role does Design Thinking play in this?

In a Design Thinking approach, the project manager spends time interviewing and monitoring client stakeholders and user representatives to determine what is obstructing the application’s usability. This, combined with user/industry research and a deep dive into problem description, aids in the development of a more comprehensive understanding of the gaps while reinventing the user experience.

In any scenario, Design Thinking adopts a multi-pronged approach. Instead of being biased, it looks at things from the customer’s perspective. It also promotes the idea that ideas, rather than people, must compete by soliciting multiple ideas and solutions. This entails assembling a multi-disciplinary team that promotes a healthy interchange of ideas and information.

How Does A Design Thinking Practitioner Manage Confirmation Bias?

When a design thinker is conscious of his bias, it is easier for him to recognize when he is utilizing it and then stop himself. While it may be difficult to abruptly change one’s attitude in certain situations, one can utilize this information to become more aware of when they may be falling victim to the anchoring bias, as they will recognize that they are more likely to experience this bias when they are sad.

Being more experienced in a task might also help to prevent anchoring bias (Welsh et al., 2014). As a result, a design thinker can practice a task to minimize anchoring bias in future experiences involving that activity. Here are some proven ways to avoid anchoring bias significantly.

Recognize and Acknowledge

The first step is to recognize and admit anchoring bias. The moment you identify its existence, it becomes easier to acknowledge it. It’s a good start to step forward if you’ve made it this far. We are less prone to fall into the bias trap if we acknowledge that our thoughts are open to such influences. So, rather than initiating a discussion and waiting for the other party to drop the anchor and make the first offer, you can beat them to it.

Take a Step Back

It is critical that you give your decision some thought unless it is absolutely necessary. You’ll be able to take a step back, recognize any anchoring bias, and look at the big picture as a result. You can collect additional information and weaken the anchor’s effect by taking your time in the decision-making process. There may be a sale of 75% off while you’re in the store.

However, what appears to be a wonderful offer could simply be the industry standard. Every other store may sell at a similar, if not lower, price. This is why it’s critical to take a step back, accept that the information available is restricted, and then gather information.

Break the Anchor

It’s critical to understand how and why the anchor exists before attempting to overcome it. We can make better-informed decisions by being aware of its existence. Instead of looking at the stock price initially, look at the company reports and fundamentals and estimate a value that isn’t based on the present stock price.

Furthermore, you may wish to begin the negotiation by dropping the anchor first. You’ll be able to control the negotiations in your court this way. Even if you don’t attain the intended result, the ultimate cost will be more favorable to you.

When our opinions are based on relevant knowledge, customer demands, and industry data rather than our personal beliefs and biases, an organization can establish a sustainable innovative culture and gain a competitive advantage. Design Thinking demonstrates how approaching an issue from a different angle and redefining the problem delivers better results and has a greater and longer-lasting influence. Designers tend to look at a scenario from the user’s point of view and come up with innovative ways to communicate and solve problems. Designers tend to look at a scenario from the user’s point of view and come up with innovative ways to communicate and solve problems. When established beliefs and assumptions are challenged, fresh solutions and new opportunities emerge.

https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/anchoring-bias

https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/anchoring

https://www.simplypsychology.org/what-is-the-anchoring-bias.html

https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-the-anchoring-bias-2795029

https://insightoutdigital.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Depositphotos_183009990_xl-2015-scaled.jpg

https://cdn.buttercms.com/LByfqndoTuyF5m3UGiBR

https://www.sagu.edu/images/thoughthub/thumbnails/2016/Anchoring.jpg

https://www.wealthmanagement.com/sites/wealthmanagement.com/files/brain-puzzle-illustration.jpg

Written By: Jimmy Jain

Edited By: Afreen Fatima

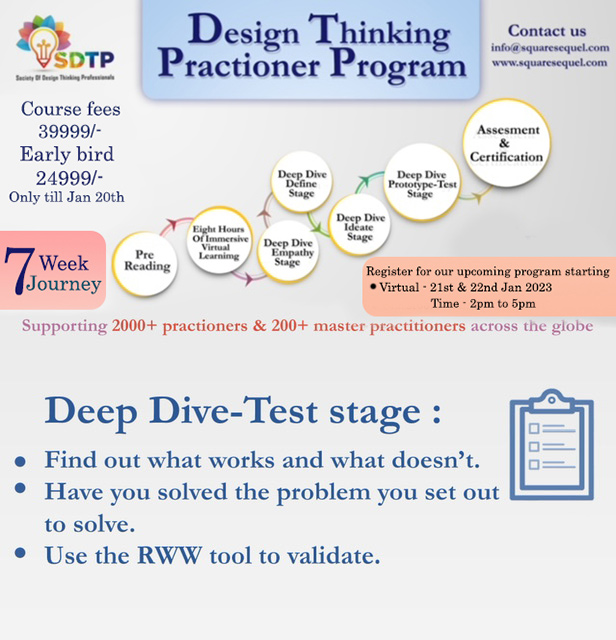

Society of Design Thinking Professionals